Estrogen is really bad for men

The published research in the past few years on the clinical effects of estrogen in males shows that there is no upside at all. And surgeries make things even worse.

Regardless of how they feel about transgender issues, most reasonable people agree that transgender people should have access to proper medical care. That expectation is a fundamental human right. However, advocacy for care and standards of care are two very different things. The former is rooted in civil rights, while the latter is based on medical science. And with the latter, the tools right now in the medical community’s arsenal almost always seem to be hormones – and, if the patients so desire, surgery. This raises the question: are hormones (and potentially surgery) the right course of action for everyone? When it comes to answering this question, state-of-the-art medical research is unambiguously clear about one thing – that estrogen is especially lethal for men (that is, those assigned male at birth).

Given all the evidence of immense iatrogenic physical and psychological harm that has been documented in the peer-reviewed research in the past few years (and, quite possibly, the absence of any upside at all), neither a medical nor a moral case can be made for administering estrogen for men with gender dysphoria. The published research also demonstrates that surgical interventions have astounding rates of postoperative complications, contributing towards reducing the expected lifespan of the patients by several decades. In this post, I will discuss this research.

Since the effects of estrogen and surgery are widespread, this post is long, and I have broken it down into several sections. I have also included a final summary section. (Furthermore, because the effects on the brain are quite involved, I have included a separate summary on estrogen’s impact on the brain.)

Effect of estrogen on the brain

Most transgender care providers will mention sterility and venous thromboembolism or VTE as the predominant risks from estrogen. However, research in the past few years indicates that its effect on the brain is at least as scary.

While not always explicitly focused on transgender issues, there has been a wealth of research in the last few years in the areas of endocrinology, neuroendocrinology, and neuroscience, which has given us a much better understanding of the effect of excess estrogen on the male brain. In 2018, researchers from the University of Leipzig, Germany, showed that an increased estrogen level is associated with depression in males.

The highlights section (right near the top) states the finding unambiguously:

(In the journal article, the statement appears as: “Depressive symptomatology was associated with increased estradiol levels in younger men, regardless of BMI.”)

The sample size – of 2244 men of age less than 60, and 1681 men older than 60 – was quite large, and the p-value was very low, so it is highly improbable that the result was a fluke. No wonder the recent New England Journal of Medicine study (that got quite a bit of attention in the press) showed no improvement in depression, anxiety symptoms, or life satisfaction among “youth designated male at birth.” Since these findings were highlighted neither in the abstract nor in the press, it isn’t surprising that they went largely unreported; to find them, look at the bottom of page 244 of the issue, Vol. 388, No. 3, of the journal:

This result is neither unique nor the first to find that higher levels of estrogen are associated with depression and anxiety among young men. In 2021, researchers from UC San Diego found similar results among adolescents in rural Ecuador: “In boys, elevated estradiol was associated with elevated depression…and anxiety scores.”

(Anecdotally, I spoke with several parents who talked about their male children descending into severe depression after a year on estrogen, so much so that even antidepressant medications did not work. More than one such child has left their studies from undergraduate or graduate school after starting estrogen therapy.)

[Before we dive into the effects of estrogen on the male body, we should clarify something about the affirming stream of literature, like the NEJM study above, straight away. They are primarily concerned about how the patients feel after the administration of hormones or surgery. They are not concerned about how the body responds physiologically to these medical interventions. To take an extreme example, if a drug like cocaine was administered to these patients who then reported feelings of euphoria, this stream of literature would report this euphoria but not consider the other long-term effects of cocaine on the body and the brain (ironically, estrogen fails even to give that “high” that cocaine does – instead, it causes depression). In this post, I review the research that addresses the question: what is the physiological effect of estrogen on the human body?]

So, why do the increased estrogen levels lead to depression among males? Over the last ten years or so, several groups of researchers – mostly in Europe – have conducted clinical studies that help us understand the mechanisms through which estrogen affects the brain, which helps us understand the depressive symptomatology among younger men after estrogen therapy. Not only that, these researchers have shown that estrogen leads not only to depression but several other (and much more alarming) neuropathologies that occur over the short, medium, and longer term. Specifically, so far, these researchers have found that estrogen:

increases the concentration of glutamate and glutamine in the brain (which is associated with diseases such as Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s disease);

decreases brain cortical thickness and volume (which is linked to patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder and is associated with lower levels of general intelligence);

reduces cortical white matter integrity (which is related to cognitive instability);

reduces gray matter (which is a prominent feature of Alzheimer’s disease);

increases the size and volume of ventricular structures (which compresses the brain from within, eventually damaging and/or destroying brain tissue);

reduces hippocampal volume (which is associated with cognitive dysfunction and is a core symptom in patients with major depression); and

reduces serum brain-derived neurotrophic factor (serum BDNF) (which is associated with an increased risk of developing MDD or major depressive disorder).

I discuss these research findings and what they mean (again, based on published research in established journals) next.

For example, in 2020, researchers from Spain administered pharmacological doses of estradiol (an estrogen steroid hormone) in adult male rats. They found that when treated with such doses of estrogen, the brains of adult male rats show changes similar to those observed in the brains of trans women. These changes were observed after just over 30 days of estradiol treatment.

(Incidentally, using rats this way isn’t unusual. Scientists have long used mice and rats in biomedical research “due to their anatomical, physiological, and genetic similarity to humans.”)

And what are these changes that are similar to those observed in the brains of trans women? The highlights of the researchers’ findings can be found right near the top of the page:

The paper highlights two changes caused by the feminization of the brain: (1) increasing the concentration of glutamate and glutamine in the brain and (2) decreasing brain cortical volume.

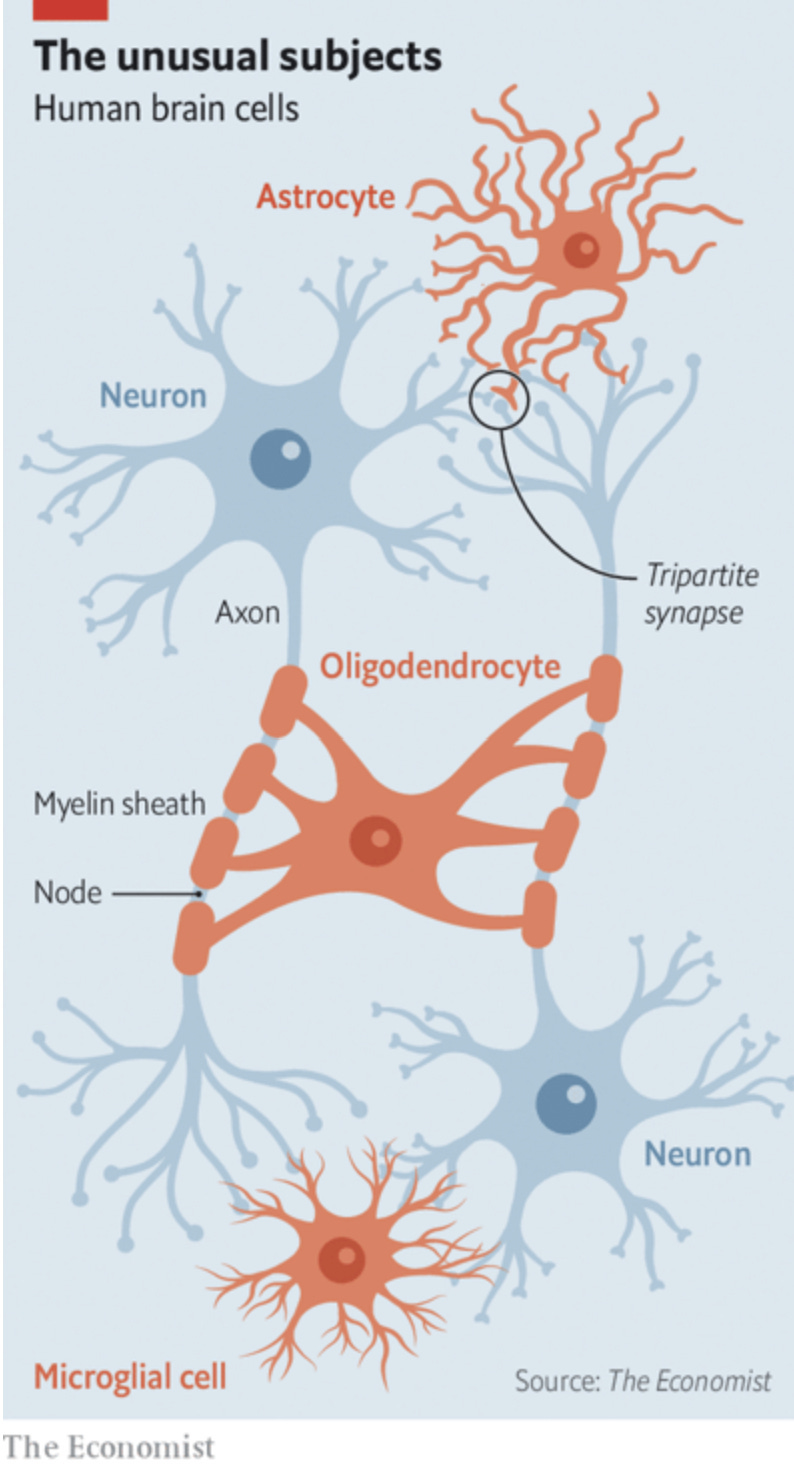

How did these changes take place? The researchers found that estrogen seemed to deplete the water content in the astrocytes and the oligodendrocytes (these are part of the glial or “glue” cells in the brain – more about them later) and in the axons.

By reducing the water content, the estradiol increased the concentration of glutamate in the brain, an excess of which, as the Cleveland Clinic notes, is associated with such diseases as Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, and Huntington’s disease. 12

Estradiol increases the relative concentration of glutamate in the brain, an excess of which is associated with such diseases as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s

The researchers from Spain also found that reducing the water content in the brain reduces its cortical white matter integrity, which is important because research has shown that reduced white matter integrity is related to cognitive instability.

Finally, the researchers found that estradiol decreased the brain cortical volume. In 2013, researchers discovered that brain cortical volume is positively associated with general intelligence in young adults (in other words, a decreasing cortical volume is associated with a lower level of general intelligence).

There are also indications that long-term estrogen treatment on transgender women leads to cognitive impairment. A recent case-control study (that was presented at the 2023 EPATH conference, no less!) with older transgender individuals (73 transgender women and 39 transgender men, in the age range of 56-84 years) who had been on GAH therapy for an extended period of time (25.8 years on average) showed that transgender women had lower scores than both non-trans men and women in information-processing speed (tested using a coding task) and episodic memory (tested using a 15-word immediate and delayed recall test), indicating that the cognitive impairment effects of estrogen persist over the long term.

(Interestingly, a new study in the British Medical Journal shows the association between estrogen-progestin therapy and dementia among menopausal women. Treating some of the unwelcome symptoms of menopause is one of the established “on-label” use of estrogen. This is where the new study comes in – a nationwide, nested case-control study from Denmark. Compared with women who had never used treatment, people who received estrogen-progestogen therapy had an increased rate of all-cause dementia. The risk went up from 21% for up to a year of treatment to 74% after 12 years of use. In most cases, the risks seemed to increase further (from the one-year level) at the >4 years mark. While such an observational study cannot prove cause and effect, the authors noted that brain MRI scans of a subset of the trial population showed menopausal HRT to be associated with brain atrophy, which in turn is strongly associated with cognitive decline and dementia. And these effects on the brain are very similar to those observed in male brains.)

More recent neuroimaging studies (in 2020) have also linked lower cortical volume and thickness in patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.

A decreasing cortical volume is associated with a lower general intelligence level and schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.

This wasn’t the first time researchers discovered that estrogen alters the male brain. In 2016, researchers at the Medical University of Vienna studied a cohort of male-to-female (MtF) and female-to-male (FtM) transgender individuals who had undergone hormone therapy and found high doses of cross-sex hormones changed the structures within the adult human brain.

Specifically, in MtF individuals, estradiol plus an anti-androgen (i.e., a substance like spironolactone or cyproterone acetate that suppresses the male sex hormones – a common prescription nowadays for men with gender dysphoria) reduced hippocampal volume and an all-round increase in ventricular structures. Both are significant findings.

Reduced hippocampal volume (the hippocampus in the brain plays a vital role in consolidating short-term memory to long-term memory and in spatial memory, which enables navigation), as researchers in Germany had discovered ten years before, “should lead to affective symptoms and cognitive dysfunction,” which, the researchers mention, are “core symptoms in patients with major depression.”

And what about the global increase in ventricular structures? Ventricles are fluid-containing cavities inside the brain. When they enlarge, they compress the brain from within, eventually damaging or destroying brain tissue.

Reduced hippocampal volume is associated with core symptoms in patients with major depression, and reduced serum BDNF levels are associated with an increased risk of developing MDD (major depressive disorder)

Incidentally, another group of researchers from Spain (two of them, Esther Gómez-Gil and Antonio Guillamon, were also in the group who researched the effects of estrogen on the brains of adult male rats in 2020) had found the same effect of estrogen on the brain – a decrease in brain cortical thickness and an increase in the volume of the ventricles – two years earlier, in 2014.

Finally, the Austrian researchers also found that reduced plasma levels of progesterone (the natural hormone in women that supports menstruation and early stages of pregnancy) in MtF individuals correlated with reductions in gray matter structures in the right hippocampus and right caudate (a subcortical structure within the brain near the thalamus). And that is important because a reduction in gray matter is a prominent feature of Alzheimer’s disease.

There was yet another instance of research illustrating how estrogen changes the brain. In 2014, researchers in Germany and Belgium showed that 12 months of cross-sex hormone treatment reduced serum BDNF levels in MtF individuals.

Why is that important? It turns out that reduced serum BDNF levels are associated with an increased risk of developing MDD (or major depressive disorder). As the NIH points out, MDD, which has been ranked as the third cause of the burden of disease worldwide in 2008 by WHO, and which is projected to leapfrog to number one by 2030, “is diagnosed when an individual has a persistently low or depressed mood, … decreased interest in pleasurable activities, feelings of guilt or worthlessness, lack of energy, poor concentration, appetite changes, psychomotor retardation [i.e., a slowing down of mental or physical activities] or agitation [i.e., a state of restlessness and anxiety], sleep disturbances, or suicidal thoughts.” The parents of young male children on estrogen therapy can relate to many of these symptoms.

Evidence from the real world backs up these findings. In 2020, researchers from the Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health presented their research showing a 37% higher prevalence of subjective cognitive decline (or SCD) – an early sign of Alzheimer’s – among transgender and gender nonbinary adults in the US. Such adults, it was reported, “were significantly more likely to report giving up day-to-day activities…needing assistance with day-to-day activities…and being unable to work or participate in social activities…compared to cisgender adults.” Furthermore, they were “significantly more likely to report difficulties in obtaining caregiving or help with day-to-day activities.”

Not only that, in 2019, a group of researchers went through the National Inpatient Sample (NIS), which is the largest publicly available all-payer inpatient care database in the United States, to analyze the psychiatric encounters of transgender and non-trans individuals over seven years. They found that the prevalence of mental disorder diagnosis in transgender patients is more than double that among non-trans patients, including anxiety, depression, and psychosis. Furthermore, transgender patients with mental disorder diagnoses had higher chronic medical comorbidities.

Let’s go back to those glial cells that we discussed earlier. In the past few years, there has been a wealth of research on these cells in our brains, and this research indicates that these cells do much more than merely being the “glue” that binds everything in the brain.

We now know that misbehaving glial cells are the culprit behind various conditions, from autism to multiple sclerosis to obsessive-compulsive disorder. Astrocytes play a crucial role in memory formation, consolidating relevant short-term memories into long-term ones (for parents who have noticed that their sons suddenly started having “brain fog” after starting on estrogen, here is a possible reason). Disorders in astrocytes are related to a wide range of different neuropathologies. There is evidence that malfunctioning astrocytes contribute to mental illnesses like schizophrenia, mood disorders such as depression and anxiety, drug dependence, mental retardation, and neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s.

Remember the research by German and Belgian researchers that showed that cross-sex hormones reduced serum BDNF, which was then found to be associated with an increased risk of developing MDD (or major depressive disorder)? Interestingly, it has been shown (in 2021) that the brains of depressed suicide victims had a markedly lesser volume of astrocytes than healthy brains. So, when estrogen reduces brain cortical volume and increases the relative concentration of glutamate and glutamine, and damages the brain in several other ways, not only do many neuropathologies follow, but it seems that the subjects also become depressed and more liable to commit suicide.

Summary of changes to the brain

To summarize the different research on its effect on the brain, estrogen:

Reduces hippocampal volume, leading to affective symptoms and cognitive dysfunction, which are core symptoms in patients with depression;

Reduces serum BDNF levels, which is also associated with an increased risk of developing MDD (Major Depressive Disorder);

Increases the concentration of glutamate in the brain, reduces gray matter, and reduces cortical white matter integrity, all of which brings about cognitive decline and is an indicator of several neuropathologies, most prominently Alzheimer’s;

Reduces the volume of astrocytes, malfunctioning of which contributes to the degradation of memory, mental illnesses like schizophrenia, mood disorders such as depression and anxiety, drug dependence, mental retardation, and neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s;

Decreases the brain cortical volume, which is associated with a lowering level of intelligence as well as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder; and

Enlarges the ventricles across the brain, compressing the brain from within and eventually damaging and destroying brain tissue.

As one can see from the findings in the literature, many of these symptoms and outcomes are interrelated and feed into each other. Furthermore, these different pathologies do not happen overnight but take place gradually, more akin to a slow-moving train wreck that reaches its climax over the next several years and decades. Transgender activists would have us believe that the heightened risks of suicide among transgender people can be attributed to their marginalization. That is definitely a possibility. However, the research from the past few years provides a more straightforward explanation for transgender women: after estrogen treatment, their brains are damaged in many different ways, causing brain disorders and depressive disorders, all of which make them gradually become more susceptible to suicide.

(In this context, it is interesting to note that among two other marginalized groups – gay men and black men – suicide is not a leading cause of death. Gay men show higher mortality risks than strictly heterosexual men; however, that increased risk comes only from HIV: “mortality risk from non-HIV-related causes, including suicide, was not elevated among MSM [men who have sex with men].” And, among black males, as a percentage of all deaths, suicide does not figure among the ten leading causes of death, but crucially, it does among non-Hispanic white males. Suicide is one of the leading causes of death among younger black males, but even there, it is significantly more pronounced among younger white males. So, marginalization does not lead either gay or black men to commit suicide in greater numbers – at least when compared to their peers.)

Finally, researchers have also noted a much higher incidence of different kinds of (benign) tumors in the transgender population within Europe (as compared to the rest of the non-trans population), though the authors concede that the long-term effects are still unknown.

Estrogen and autoimmune diseases

Another effect of estrogen among trans women is its role in autoimmune diseases.

Adult women are disproportionately more prone to allergies, asthma, and autoimmune diseases than men (interestingly, young boys have more allergies than girls, but the ratios flip completely after puberty). However, the massive spike of synthetic estrogen hormones changes that equation for trans women. For example, one parent I talked to mentioned how their son used to be the prime caretaker of the cats in their house and is now (after hormones) utterly allergic to them.

Adult women are disproportionately more prone to allergies, asthma, and autoimmune diseases than men. However, the massive spike of synthetic estrogen hormones changes that equation for trans women.

Estrogen skews the body’s immune responses toward allergy, worsens asthma attacks, and its harmful effects gradually progress to more severe autoimmune diseases.

There are case studies of increased immune-mediated rheumatic diseases (IMRD) such as rheumatoid arthritis, spondyloarthritis (characterized by low back pain), systemic lupus erythematosus or SLE (the most common type of lupus, where the body’s immune system attacks its tissues in joints, skin, brain, lungs, kidneys, and blood vessels – there is one case study of a trans woman developing SLE 20 years after sex-reassignment surgery and prolonged estrogen therapy), and vasculitis (where blood vessels – both arteries and veins – are destroyed), as well as the onset of other autoimmune diseases among trans women.

Systemic sclerosis, or SSc, seems to be a particularly vexing issue with estrogen supplementation. It often shows up as tightening of the skin and contracting of the fingers (see a photo below), but it affects the joints and many different internal organs. In a letter sent to the Journal of Clinical Rheumatology in December 2021, the authors (from the Feinberg School of Medicine at Northwestern University) mention that “estrogen supplementation could play a pathogenic role in SSc and its diverse complications” and then go on to describe a case of a man with previously limited and contained skin-related SSc. After starting estrogen treatment, these conditions suddenly became acute and developed into scleroderma renal crisis, a life-threatening complication with the abrupt onset of severe hypertension accompanied by rapidly progressive renal failure.

One parent I met at a parent group mentioned how their son suddenly developed Crohn’s disease after starting hormone therapy – already, his daily regimen is up to 8 medications. A 31-year-old male detransitioner mentions developing scoliosis and osteoporosis after hormone therapy, both of which, while not autoimmune diseases themselves, are linked to (as outcomes of) autoimmune diseases.

Our understanding of these diseases (76 of them, by the last count), when the immune systems that are supposed to defend our bodies from diseases but attack us instead, is still evolving. Many of them have no known cure. However, we now know that nearly 80% of the autoimmune sufferers are female, and it is clear that many autoimmune diseases “are driven by estrogen,” specifically by spikes of estrogen in the body.

It is clear that many autoimmune diseases “are driven by estrogen,” specifically by spikes of estrogen in the body.

Research has also shown a “strong association” between gender identity disorder and multiple sclerosis in trans women, indicating “a potential role for low testosterone and/or feminizing hormones on MS risk” among natal males. (Remember the association between misbehaving glial cells and multiple sclerosis that I discussed earlier.)

Estrogen’s effect on diabetes and the liver

Estrogen also decreases insulin sensitivity (also known as increasing insulin resistance among diabetes patients) in trans women, which is a sign that the body is having difficulty metabolizing glucose, which can indicate broader health problems such as high blood pressure and cholesterol levels.

And while we are dumping on poor estrogen, let us also note that among women, higher doses of estrogen have been associated with several liver-related complications, including “intrahepatic cholestasis, sinusoidal dilatation, peliosis hepatitis, hepatic adenomas, hepatocellular carcinoma [i.e., liver cancer], hepatic venous thrombosis and an increased risk of gallbladder stones.” While these ailments were more commonly seen with higher doses of estrogen, they have also been described with lower estrogen hormone replacement therapy doses. A recent study has found that “use of estrogen therapy is a likely risk factor for the development of gallstone pancreatitis.”

Estrogen and the cardiovascular system

Moving on to cardiovascular risks of trans women on estrogen, a large-scale study from 2018 among transgender patients in the US showed that, compared to men, the incidence of venous thromboembolism or VTE (or blood clots, which include deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism) among trans women is 50% higher within the first two years of hormone treatment and more than five times higher in follow-ups beyond two years. The incidence of ischemic stroke (when the blood supply to part of the brain is interrupted or reduced, resulting in the brain cells dying within minutes) is 30% higher within the first two years and nearly ten times higher in follow-ups beyond two years. The authors concluded that “these results… indicate the need for long-term vigilance in identifying vascular side effects of cross-sex estrogen.”

The risk of VTE is more than five times higher beyond two years; the risk of ischemic stroke is nearly ten times higher beyond two years.

These results weren’t outliers either – they were replicated in 2019 by researchers at the Amsterdam University Medical Center (where the Dutch gender clinic is located).

Estrogen and cancer among men

Other than the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma or liver cancer I mentioned earlier, an “ample body of evidence” suggests that “estrogens may play a critical role in predisposing, or even causing, prostate cancer.”

And in 2015, in the Journal of Clinical Oncology, researchers mentioned that “circulating estradiol levels showed a significant association” with the occurrence of breast cancer among men.

Still, we must be thankful somehow – if “thankful” is the word I seek. Because women – those born with ovaries and uteruses – have to deal with cancers in those organs, and for those cancers, once again, estrogen is to blame.

My conversation with an elderly trans woman

At this point, it seems pertinent to mention my recent conversation with a 70-year-old trans woman (who now identifies as a man after forty years of hormones and surgeries and living as a woman). This is something that even GLAAD would recommend: “Listen to trans adults who can tell you about their experiences.” And so I listened to this trans adult as they told me about their experience with hormones and surgery.

The man suffers from many of the diseases I mentioned above: several heart attacks (the first one before they turned forty), hypertension, rheumatoid arthritis, scleroderma, low back pain, allergies, asthma, retinal detachment in one eye, and loss of sight in another, and a cocktail of medication for his heart. He has had stones in his liver (“the doctors had never seen anything like that”), kidney, gallbladder, and saliva ducts (“the size of lime pits, and they had to operate inside my mouth to get them out”). I could not help but note that he suffers from many of the diseases described in the literature – and several more (he mentioned that he knows several MtF people like him who suffer from a retinal detachment, for example). He has not been intimate with a woman for over 30 years – all that disappeared after his orchiectomy (the surgical procedure to remove one’s testicles). Several of his friends – all transgender – have either succumbed to disease or committed suicide. Fortunately, as a vet, he has the VA to go to – a luxury that many young men will not have.

He suffers from many of the diseases that are described in the literature – and several more.

I present this man’s story (or that of the other young men whose parents have spoken to me) not as an anecdote but as part of a larger narrative: these men suffer from many more medical complications compared to their non-trans counterparts. In 2017, by comparing claims between transgender and non-trans Mediclaim beneficiaries, it was found that the former have more chronic conditions than the latter, with more cases of asthma, autism spectrum disorder, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, depression, hepatitis, HIV, schizophrenia, and substance use disorders. The transgender Mediclaim beneficiaries “also had higher observed rates of potentially disabling mental health and neurological/chronic pain conditions, as well as obesity and other liver conditions,” compared to the non-trans beneficiaries.

At this point, we should also remind ourselves that the recent research probably vastly undercounts both the incidence of disease and the diseases themselves.

At this point, we should also remind ourselves that the recent research probably vastly undercounts both the incidence of disease and the diseases themselves. Historically, the medical establishment could be least bothered by what is happening to a mostly impoverished and marginalized population that stayed in the shadows and was considered an aberration by the general public. There was no money to be made from the transgender population for Establishment Medicine. When a transgender person died, nobody cared, and there was no autopsy or investigation, nor was there any medical history to follow up on. A few “doctors” handed out off-label medication or performed surgeries away from the spotlight. Even if these doctors came to know or suspect anything, they had no incentive to publicize those findings to the general public and “out” themselves in the process. All the while, these people died an early death. And those premature deaths were staggering.

Mortality after hormones

Depression, mental and neurological disorders, cardiovascular diseases, autoimmune diseases, different types of cancers, and increased suicidal thoughts – no wonder the overall mortality risks of transgender women are so much higher than the general population (published in The Lancet in 2021, this landmark study looked at the mortality risks of transgender people in the Netherlands over five decades, with data from the Amsterdam clinic, between 1972 and 2018).

The deaths were attributed to cardiovascular disease (21%), cancer (32%), HIV-related disease (5%), and suicide (7.5%). Significantly, even though the risks of dying from HIV have decreased over the past few decades (and presumably, the stigma against transgender people is lower now than it was 50 years back), the mortality risks did not reduce over time. These high mortality numbers have been replicated among US transgender patients by researchers at the University of Michigan and Brown University in their research published in 2022.

One way to think of this data would be to compare the probability of dying for a transgender woman who has undergone hormone therapy to that of a non-trans man (the differences are even starker when compared to a non-trans woman). Using the US transgender data (from Appendix Table A2 in the study above), we can reconstruct and compare the probabilities of a trans woman and a non-trans male being dead at various ages:

At thirty, the probability of dying for both populations is the same. However, within the next ten years, the probabilities start diverging. So, suppose you are the parent of a young man who has started hormone therapy. In that case, you have nearly a 1-in-10 chance that you would be holding a dead child in your hands before they reach fifty – which is more than three times the probability for a parent whose child has not undergone hormone therapy. And there is a 1-in-5 chance that your child will be dead before sixty – and because of all the associated physical and mental ailments, it will probably be a drawn-out, lingering death with many hospitalizations and emergency room visits along the way.

The parent of a young man who has started hormone therapy has a 1-in-10 chance that they would be holding a dead child in their hands before they reach fifty – more than three times the probability for a parent whose child has not undergone hormone therapy.

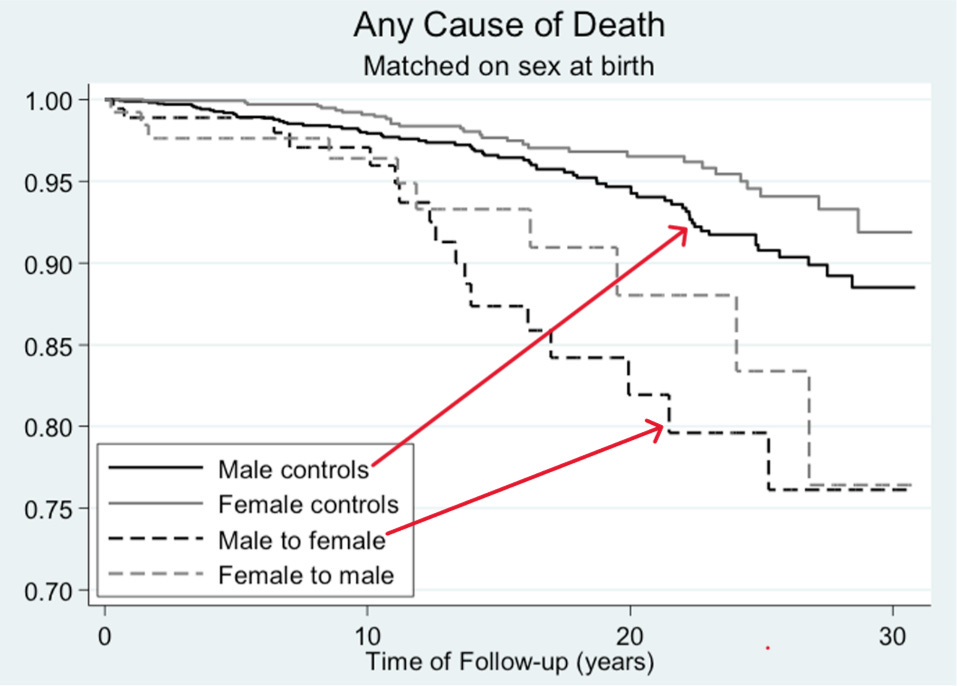

Postoperative complications after surgery

The mortality rates are even worse after surgery than they are after hormones – which is somewhat ironic since, if the activists were to be believed, the surgeries should have led to a more fulfilling life for a transgender woman in their quest to become their “authentic” self. A graph in the paper (shown below) shows the probability of dying from any cause as a function of time after surgery (unlike some research that reports outcomes after a few years of follow-up at most, in this research, the authors doggedly followed up with the patients long after their surgery and obtained their mortality information from the Swedish national registers. These mortality data were then compared to population controls matched for age and gender). As one can see, the chances of dying just a little over ten years after sex-reassignment surgery are the same as what would have been after 30 years if the person had not undergone surgery.

One possible reason behind these accelerated deaths? The postoperative complications – and these are widespread, right from the very beginning.

In December 2022, researchers published data from Canada’s first vaginoplasty postoperative care clinic, indicating that nearly a quarter of the trans women who were operated on accessed care in the first three after surgery, and more than half of them sought care within the first year. More than three-fifths (61.3%) were seen for more than one visit and presented with more than two symptoms or concerns.

Common patient-reported symptoms during clinical visits included pain (53.8%), dilation concerns (46.3%) (the body identifies the neovagina as a gaping wound, and so it has to be dilated for life, including multiple times daily during the first year – the aftercare regimen runs into eight pages), and surgical site/vaginal bleeding (42.5%). Sexual function concerns were also common (33.8%), with anorgasmia (inability to orgasm) (11.3%) and dyspareunia (painful intercourse) (11.3%) being the most frequent complications. The most common adverse outcomes identified by healthcare providers included hypergranulation (38.8%), urinary dysfunction (18.8%), and wound healing issues (12.5%).

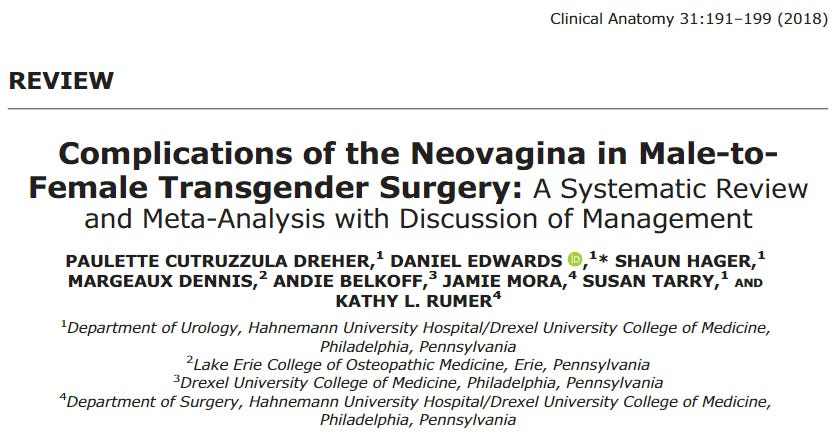

We aren’t done yet. An older review of the literature from 2018 on complications of the neovagina in trans women after surgery shows an overall complication rate of 32.5% (i.e., about one in three cases) and a reoperation rate of 21.7% (more than one in five cases) for “non-aesthetic reasons.”

Another paper from 2018 discusses various neovaginal complications in trans women: 15% suffered from the stricture of the neo-urethra, leading to urinary tract infections. 10% of the cases developed scar tissues in the neovagina, causing it to become narrower and shorter. Another significant concern was “intravaginal hairballs” (self-explanatory but possibly hard to visualize). Other complications include vaginal prolapse (when the top of the vagina weakens and collapses into the vaginal canal) and recto-vaginal fistulas (a tunnel between the vagina and rectum, leading to rectal discharge through the vagina, including during sexual intercourse).

The surgeries do not help with their psychological outlook either. One study from 2019 initially claimed that they did, only for the researchers to retract their claim a few months later: “the results demonstrated no advantage of surgery in relation to subsequent mood or anxiety disorder-related health care visits or prescriptions or hospitalizations following suicide attempts in that comparison.”3

One can imagine how difficult it would be for anyone to come to terms with these setbacks – especially if they had been promised a life of fulfillment afterward.

Can you imagine how it feels to realize that everything you were told was lies and there is no way to turn the clock back? That all those “brave” statements you made are now seen as hollow remarks made by a callow young man without mental maturity? All of us have made our share of stupid statements or done stupid things in our youth. But then we have the benefit of time to rectify those misadventures. That is a luxury that will be denied to these young men.

However, those who can muster the courage to talk mention that their life has been a “living hell since then.” Another detransitioner asserts, “This is not rare.”

Many of these complications will remain with the patients for life, affecting their basic day-to-day activities from morning till night (one such account makes for harrowing reading: “managing the trickle of urine from my constricted urethra after going to the toilet, the occasional shooting pain and the despair of my own stupidity”). Will it be a surprise if many succumb to these complications – or commit suicide – so early in their lives?

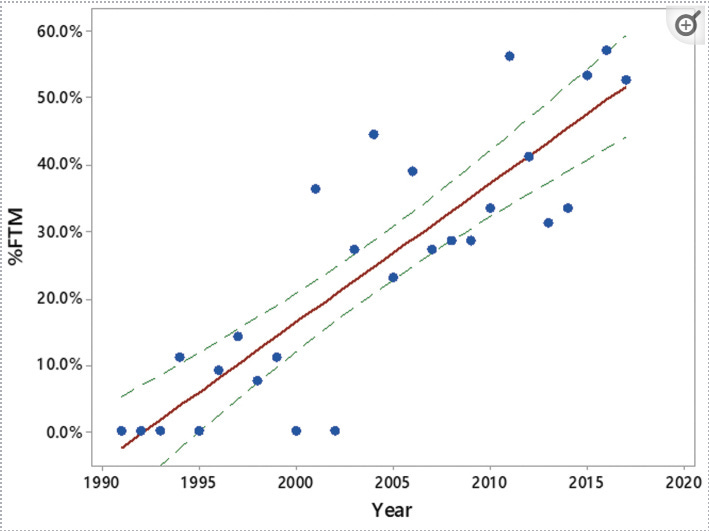

Reading all this, one might wonder how we hear stories of people doing better after hormones. One possible reason is the very different effects of the two hormones, estrogen and testosterone. When it comes to hormone replacement therapy among young women, research has shown that testosterone can lift one’s mood (to be clear, though, these research report their findings among men), and so it is plausible that some young women will find the shots of testosterone mood-enhancing (as one female detransitioner said, it made her “aggressive and horny”), even if those changes are often relatively small and transitory. In recent years, there has been a preponderance of young women among those identifying as transgender. The graph below shows how the number of women identifying as FTM (i.e., female-to-male) transgender as a percentage of the overall transgender population has changed from low single digits in the 1990s to over 50% in the past decade, which implies that the share of the new generation of women in the past two decades who identify as transgender would have to be significantly more than the men – and increasing – to flip this overall ratio within these two decades.

As a result, researchers who have combined responses from (natal) young men and women often have samples that over-represent (natal) females (e.g., 61% of the sample in the NEJM (2023) study consists of natal females). Consequently, such research has sometimes indicated some – albeit very modest – positive psychological outcomes after a few years within the overall sample, thanks possibly to the effects of testosterone. (The other impact of this recent inversion of the ratios is that we do not have as much long-term data about the effects of testosterone as we have about estrogen: “[a] major limitation in the study of testosterone therapy for transgender men is a paucity of high-quality data due to a shortage of randomised controlled trials…few prospective and long-term studies, the use of suboptimum control groups, loss to follow-up, and difficulties in recruitment of representative samples of transgender populations.”)

But dig down deeper to look at the outcomes for just the young men (as the researchers did in the NEJM paper or as one did with this 2022 PLOS One paper). None of them report any positive outcomes for the youths assigned male at birth (for example, a careful analysis of the data from the PLOS One (2022) paper indicated that, contrary to the researchers’ original claim that access to the hormones is “associated with favorable mental health outcomes,” estrogen is associated with increased suicidality among (natal) men).

The clinical research on the effect of estrogen on males that I discussed earlier shows why these results, which fail to show any psychological improvement for men, aren’t an anomaly but actually to be expected.

Summary and concluding remarks

The TL/DR version of this post: Hormones will not help the gender-dysphoric young men with their psychological outlook – the results from the NEJM (2023) study or the more comprehensive Journal of Clinical Medicine (2021) study have conclusively shown that.4 Instead, it will damage the brain in many different ways, resulting in depression. Then, as the years roll on, the physical effects will start – with allergies, asthma, heart diseases, diabetes, liver diseases, a host of autoimmune diseases, and possibly even different types of cancer. And most cruelly, the brain will start shrinking, diminishing their mental capabilities and causing neuropathologies from Alzheimer’s to schizophrenia.

It will not be an overnight phenomenon; rather, it will be a slow-moving train wreck. One by one, the effects will start to pile up – to paraphrase Hemingway, slowly at first and then rapidly. Within a few months, the initial placebo effects, if any, would have long disappeared. Once the irreversible changes are in place, and the spotlight has moved on from these young men, the realities of the physical and mental ailments in their day-to-day existence will take over – and stay with them for the rest of their tragic lives. The early cognitive decline will result in their giving up daily activities. They will increasingly be unable to work or participate in social activities, which will probably further hasten their isolation and cognitive decline.

At the same time, there will be so many diseases to keep track of, along with so many doctor visits and hospitalizations, so many bills and co-pays, and so many encounters with insurance (which, if they are without a job, might not be there – especially in the United States). Trying to keep track of such things naturally gets more complicated as one becomes older. Imagine trying to do all these things when you are alone and suffering from cognitive decline.

By the 10-year mark, all the physical and neurological disorders will begin to affect the lives of these men significantly enough to affect their overall lifespans – and it will get progressively worse after that. Surgeries, if these men are unfortunate enough to opt for them, will push their tragic stories into the realm of the horrific and macabre. Finally, due to all these physical and mental complications, they will die a painful death – possibly decades sooner than their counterparts who did not medicalize.

There is no other way to say it: It is all horribly bad news for these young men on hormones. Right from DAY 1. An analogy might help here to understand the absurdity of the situation here. It is as if the medical community is saying that since cancer patients are suffering, we should administer cyanide capsules because some “experts” within the community have suddenly decided, without evidence, that cyanide will help these patients. The patients desperately need help, but cyanide is not the answer.

This does NOT mean that these young men aren’t suffering. They absolutely are. One does not decide to start with off-label and clinically untested medication for the rest of their life unless they are suffering immensely. And it is also true that when they hear people questioning their beliefs, what they hear (or perhaps have been conditioned to hear) is an outright negation of their very existence. Such sentiments, however, present a false dichotomy to these young men: “Medicalize or die.” While the truth is more along the lines of “Medicalize, and then die.” Far from being the panacea that they are seeking, for young men suffering from the sense of unease that they have because of a mismatch between their biological sex and their gender identity, there is no upside whatsoever from either the hormones or surgery.

It also does NOT mean that there is no hope for these young men. Advances in psychotherapy are helping many of them cope with their gender dysphoria. For example, in the journal Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, a researcher described “a special adaptation of group psychotherapy as a psychological treatment for people with a variety of gender identity disorders,” which “can be used as an alternative to…hormonal and/or surgical interventions for transgender people.” The research drew from “a UK specialist pilot for such a treatment service.” As more attention is drawn to these young people suffering from gender dysphoria, many more promising (and most importantly, evidence-based) approaches will emerge. After all, there’s a vast market, “larger than the entire film industry,” to cater to.

When it comes to estrogen, however, the evidence base is conclusive. If it were any other substance we were talking about (for example, a drug like cocaine) with such demonstrated evidence of long-term harm to the body and mind, neither the medical establishment nor society would have allowed their use.

If our medicine is to be guided by evidence, is there any scientific reason to consider treating men with estrogen differently? And how long can the medical establishment – e.g., the American Medical Association, the American Psychiatric Association, or the Endocrine Society – continue to disregard this evidence of iatrogenic harm? For every day that they fail to act, some more young men are being pushed further toward their untimely death.

Researchers have known since 2006 that higher levels of estradiol are associated with cognitive decline, Alzheimer’s Disease (AD), and AD with cerebrovascular disease among older men.

The article from the Cleveland Clinic goes on to state that too much glutamate in the brain is also associated with other diseases like amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (i.e., Lou Gehrig’s disease), multiple sclerosis, stroke, fibromyalgia, and chronic fatigue syndrome.

Reanalysis of the data indicated that not only did those who refrained from surgery fared no worse, but they also had half as many serious suicidal attempts. However, this difference did not reach the threshold of statistical significance.

There are lots of poor studies in the area of the psychological effect of hormones, leading to an evidence base that is, as The BMJ recently noted, “preliminary or inconclusive” (The Economist, after surveying the findings from many international medical bodies, also arrived at the same conclusion). Many are quite poor, and then some are truly awful in their deception and spin, claiming things that even their flawed methodology does not show. The two studies mentioned in this paragraph – NEJM (2023) and Journal of Clinical Medicine (2021) – report clinically-observed data from large-ish cohorts (315 and 873, respectively) followed over a somewhat more significant period of time (2 and 3 years, respectively), which makes their conclusions, many drawbacks aside, somewhat more trustworthy.

Thank you for this amazing research. I just sat through a lecture at my medical school by a woman with a PhD from OHSU gender clinic. She presented claims that gender affirming care for minors is "curative and preventive." Her presentation had ZERO references to back up her claims. She also contradicted herself multiple times. One such contradiction was in her attempt to debunk what she called a myth, that adolescents could outgrow gender dysphoria. Her debunk went like this: “If an adolescent is in puberty, it is unlikely a phase. However, adolescence is a time of identity exploration and experimenting with expression. By supporting them in their gender identity, we can help facilitate healthy exploration of all the aspects of their identity.” Exact quote. This woman claims to be a professional in the medical field and yet she presents this topic without references, contradictions, and outrageous claims. Unbelievable hubris. What is sounds like from her presentation is she is knowingly and willingly sterilizing young people from poor families, POC and homosexuals.

Thank you. My son is a conscientious and kind doctor in the UK, and it frightens me that he still believes that puberty blockers and hormones are acceptable treatments for young people.

My words are falling on deaf ears even though I study gender issues, having worked in NHS mental health.

He doesn't work in this field luckily. But people like him need to read this...and listen to the detransitioners who are dealing with the personal fallout.